In 1992, John Gray published a best-selling book that was called, “Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus”. This book sold more than 50 million copies and spent 235 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. Part of the reason that this book was so popular was because it pointed out that the most common relationship issues that were occurring between men and women was the result of a fundamental psychological difference between the genders. While men had an emotional need for trust, acceptance, appreciation, admiration, approval, and encouragement, women needed caring, understanding, respect, devotion, validation, and reassurance.

In one example of a misunderstanding, a woman bitterly complained that her husband never took her out. Insofar as this couple had just gone on an outing with their children, her spouse was understandably confused. As it turned out, what the woman meant was that her partner hadn’t been spending private alone time with just her. This made her feel unloved, unappreciated, and undesirable.

Just as there are gender differences between how neurotypical people communicate, so too are there differences between how people with autism also communicate.

Those of us who are on the autistic spectrum value:

- Telling the truth

- Getting to the point in any given communication

- Problem solving

- Having the opportunity to share our special interests

Given issues with our neurology we also need:

- Plain speech

- Time to process what was just said

- Opportunities to interact in a quiet setting

- The freedom to self-stim

- To not be touched by others without permission

Telling the Truth:

Although we are capable of lying, our literal mindset prefers honest speech. As a result of our neurology, we are not a good people to turn to for reassurance unless one really wants candid feedback. For example, if a woman were to ask me if the dress she was wearing made her look fat, a much younger version of yours truly might have said, “You look like a sausage about to explode out of its casing.”

Time and experience from years of having interacted with allistic (non-autistic) people have since taught me that the person in question was likely seeking reassurance. Insofar as this understanding has not made me any better at lying, I have learned to sidestep such questions by offering a non-committal reply such as, “That’s a good color.” The woman in turn will often assume that I meant, “That’s a good color ON YOU,” which is not what I just said. Were she to preen and to then ask for more reassurance, she would likely not enjoy my response because my ability to prevaricate is quite limited.

The misunderstanding: As a result of what has been described as our brutal honesty, we are sometimes misunderstood as being insensitive and hurtful instead of being viewed as truth tellers.

While I understand the concept of a white lie, to me a lie is still a lie. The closest I will come to lying is when I omit to say the whole truth. For example, a teacher colleague once gave me a large plastic container of the worst chili that I’ve ever had in my life. Since she was anxious for me to try it and to then give her my opinion, I realized that this was likely a situation that would require the use of a white lie as a way of not hurting her feelings. Since I couldn’t bring myself to do this, I sidestepped the truth and said, “I’ve never tasted anything like this.” My colleague assumed I liked it and literally danced her way out of the kitchen.

I took the chili home, reheated it, and seasoned it with salt, pepper, granulated garlic, hot sauce, beef bouillon, ground cumin, chili powder, and a touch of sugar. I then ate two bowls of this chili for dinner and was able to honestly tell my colleague that I had eaten the chili for dinner. I did not tell her what I had to do to make the chili palatable.

Getting to the point in any given communication:

It is often frustrating to people with autism that others do not simply get to the point. Since neurotypicals have a need to socialize, they often chit-chat about what seem like completely inconsequential things prior to getting to the main point of what they actually wanted to say.

Since I once spent 8 years teaching at American schools abroad in Saudi Arabia and Lebanon, I think that Arab allistics are even worse than Americans when it comes to casual conversations. In addition to small talk, an Arab will often want to share tea. I am not a big fan of tea, particularly when it’s sugary sweet and served on hot day. I would much prefer a tall glass of heavily iced, cold water. The sharing of tea prolongs the opportunity of simply “getting to the point.”

While neurotypicals seem to value the social component of any communication, autistic people simply want to convey or to receive information.

We would much prefer short and to the point conversations like, “Hey Jim, do you have a copy of the report that Melanie sent? Could you email me a copy? Thanks!”

The misunderstanding: As a result of our preferred communication style, we are often seen as being abrupt, dismissive, and rude. Some people have also accused us of being insensitive simply because we regard having to look at yet more pictures of your newborn infant as being completely irrelevant to our purpose in having approached you.

Problem Solving:

“George doesn’t understand me,” sobbed one of my teaching colleagues. It was after hours and I had been grading papers in my 4th grade classroom. A tearful colleague had come into my room and was sharing her (latest) relationship issue.

“All he wants to do is to talk about his career, to brag about his latest promotion, and to show off how much money he makes by buying me more jewelry or taking me out to eat for an expensive meal.”

I raised an eyebrow. Why did this person keep telling me about her relationship issues? Was it because I was her nearest neighbor? Was it because I was the only male 4th grade teacher at our school and she needed a guy as a sounding board? Was it because I had forgotten to turn off the classroom lights and to lock the door so that I could sit at my desk (which was out of sight of the hallway) and grade my papers in peace?

Since many of us on the autistic spectrum are natural problem solvers which the Journal of Human Brain Mapping (2019) has said have the ability to solve problems 40% faster than non-autistics, I made the (erroneous) assumption that this woman had come to me for relationship advice.

“You should dump him,” I said.

“WHAT?” demanded the startled woman.

“I said, ‘You should dump him.’ If he doesn’t appreciate or respect you then it follows that he isn’t worth your time. Dump him and find someone (For the love of a merciful God, PLEASE NOT ME) who will make you happy.”

“YOU DON’T UNDERSTAND ANYTHING!” huffed the woman who then flounced out of my classroom.

I remember rolling my eyes while quietly agreeing with the woman.

The misunderstanding: Since autistic people are not good with inferences, most of us will assume that if you approach us to talk about a personal problem, it must be because you want us to propose a solution. If you simply want us to listen, you should say this at the outset. If you really feel compelled to share your problems with somebody else, you should consider scheduling a session with a therapist who is actually paid to listen to whatever your insecurities may be.

Plain Speech

“I want you!” said Tina (not her real name) over the phone at 3 AM. Since Tina was a friend and since we had a friendship agreement, I knew that this couldn’t possibly have been an amorous phone call.

“What do you want me for?” I asked.

“I NEED YOU!”

“For what?”

“Just GET OVER HERE!”

“Okay,” I replied, “Just don’t blame me if I come over and I didn’t bring the right tools.” Given the lateness of the hour, I assumed that Tina was having some sort of household emergency which likely involved a dripping pipe or a clogged toilet. I went over to Tina’s home with a wrench and a toilet plunger.

“What seems to be the problem?” I asked when Tina answered the door. I held a wrench in one hand and a toilet plunger in the other. Despite the fact that it was a cold night, Tina was wearing a sheer nightie. I averted my eyes because it wasn’t appropriate to ogle one’s friend. I also observed that given how cold it was, Tina ought to have considered dressing more warmly.

Tina took one look at my tools and slammed the door in my face. It would not be until years later that someone explained to me that Tina had wanted to change the nature of our relationship and that she had chosen a non-verbal method of communicating this thought. For my part, I remain miffed that she was upset with me when I was not the person who violated the friendship agreement. I was also annoyed that I went over to her home at 3 AM to help her, only to have her slam her door in my face.

The misunderstanding: Since people with autism have literal mindsets, we often misunderstand or completely overlook the subtle communication that is often conveyed with innuendo, figurative language, sarcasm, facial expressions, body language, tones of voice, and women who are wearing sheer nighties.

In a speech pathology class, I recently learned that the meaning of as much as 60% of what people say is modified through the use of nonverbal language. Since we are also inclined towards truthfulness, please don’t expect us to deviate from our given word. A friendship agreement is a friendship agreement and one does not “hit” upon one’s friends. If Tina had wanted to change the nature of our relationship, she should have articulated her thoughts by actually saying what she meant. Insofar as I am not good at reading body language, facial expressions, or understanding tones of voice, the message she was trying to convey through her nonverbal communication completely eluded me.

Time to process what was just said

People with ASD (autism spectrum disorder) do not have a natural understanding regarding the rhythm and cadence of a conversation. It takes time for us to process what was said, to decode meaning, and to formulate a reply. All of this takes time and given how fast some conversations evolve, by the time we have come up with a relevant reply, the conversation has often moved on to a completely different topic and we are left sitting on the sofa feeling ignored and completely misunderstood.

The misunderstanding: As a result of our need for time to process and understand what was just said, autistic people are sometimes seen as “shy” or completely “aloof”. While many of us are shy, the fact that autism is a spectrum disorder means that some autistic people are actually quite extroverted.

Opportunities to interact in a quiet setting

At the faculty party prior to the start of the news school year, the principal’s stereo was rocking with an oldie but goodie from the 1950’s. Faculty members were dancing. A dozen conversations were taking place throughout the living room. People were walking past the refreshment table where I was standing in the corner behind the table as I pretended interest in an art print.

“Hello,” chirped a voice. “I’m Mindy. How are you doing?”

I stared at Mindy. It was all I could do to not run away screaming. My senses were being overwhelmed from the music, the bright lights, the on-going conversations, the dancing, and the movement as people approached and left the refreshment table. My heart felt as though it was about to explode through my chest. Although I heard and understood what Mindy had just said, I was so stressed out that I lacked the capacity to respond.

Since I was not clinically diagnosed with autism until I had turned 60 years of age, I realize in retrospect that I was likely having a meltdown at the time that Mindy approached me. A meltdown is described as an intense and uncontrollable response that results when a person with autism feels overwhelmed. In this, we are like computers that need to reboot. The “rebooting process” will take anywhere from 20 minutes or longer for us to partially recover depending upon the amount of emotional trauma and whether or not the situation that led to the meltdown has been resolved.

“Ah, that’s David. Don’t expect him to reply. He’s a stuck up snob who thinks that he’s better than the rest of us. I know him. He’s no better than the rest of us,” sneered a male colleague. “Hi, I’m Jim,” he said as he stuck out his hand. “Wanna dance?”

The misunderstanding: Since we have sensory issues, most of us will never be at our personal best in loud, brightly lit, crowded and noisy areas. Too much sensory input has a tendency to overwhelm our mind’s ability to process information. We do better when interacting in small groups that are in quiet areas with subdued lighting. People who don’t know or understand what we’re experiencing often make cruel and insensitive assumptions about our behavior.

The freedom to self-stim

Self stimming involves the use of repetitive motions that may include but are not limited to swaying back and forth, pacing, and twitching one’s fingers. People with autism often engage in this behavior as a way of reducing personal stress. Since many of us do not like to be touched, self stimming is said to provide the emotional reassurance that neurotypicals get from being hugged.

Since years of experience have taught me to hide such motions, I will often put my hands deep into my pockets where my hidden fingers will twitch. I will also put my hands behind my back so that I may twitch my fingers and wag my hands.

The misunderstanding: People who observe us self-stimming will at best think that we’re eccentric. At worse, they will assume that we have issues with executive functioning which is our ability to self-control. Unkind people will even suggest that we’re intellectually challenged.

To Not be Touched Without Permission

A few years ago, I taught Culinary Arts at a high school. Another teacher whom I will refer to as Lucy which is not her real name, was a serial hugger. For reasons that I lack the ability to understand, she was a very physical person who liked to hug her colleagues.

Since I do not like to be touched, the first time she tried to hug me, I circled around a kitchen supply table to avoid her. She thought that we were playing and decided to chase me. As she began to speed up, I responded in kind. “STOP IT!” I found myself shouting. “DON’T TOUCH ME! STOP IT!”

When she didn’t stop and continued to chase me with a manic grin on her face, I ran out of the kitchen, across the hallway, and into the administrative offices.

“Are you okay? What’s wrong?” asked my immediate supervisor.

Since I had been driven into a meltdown at this point, it was some time before I could recover enough to report that a colleague had been chasing me and that she hadn’t responded to a request to stand down and to not hug me.

Admin talked to this woman and told her to leave me alone. Since she persisted in wanting to visit me and kept approaching me within my Culinary Arts kitchen after school despite my requests that she keep her distance, admin had to speak with her two more times before she began to leave me alone.

Please don’t hug us, especially if we have asked you to not do so. While most of us may understand that you were simply trying to be friendly, your need to demonstrate how friendly you are should not outweigh our desire to not be touched.

The Implications for HR

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, only 22.5% of all disabled adults in the United States are actually employed. Although autistic people on average have higher than average rates of intelligence and are often highly educated, we are only employed at HALF of the rate of other disabled people.

Part of the problem appears to be the traditional way in which HR interviews new applicants. An applicant who has poor masking abilities will fail to make eye contact, will flinch when shaking hands, and will often have a weak handshake. Since he or she will be visibly nervous during the interview process, the recruiter may notice that the applicant is fidgeting while persistently checking the time on his or her watch.

The unfortunate impression that is given as the result of this behavior is that the applicant is seen as untrustworthy and that he or she was eager for the interview to end. Such applicants rarely make it past the initial screening.

Given how increasingly competitive the job market is becoming as baby boomers like myself are aging out and retiring, some companies like Chase, Microsoft, Home Depot, CVS Caremark, and Walgreens have autistic friendly hiring programs that bypass HR initial screenings to look at qualifications.

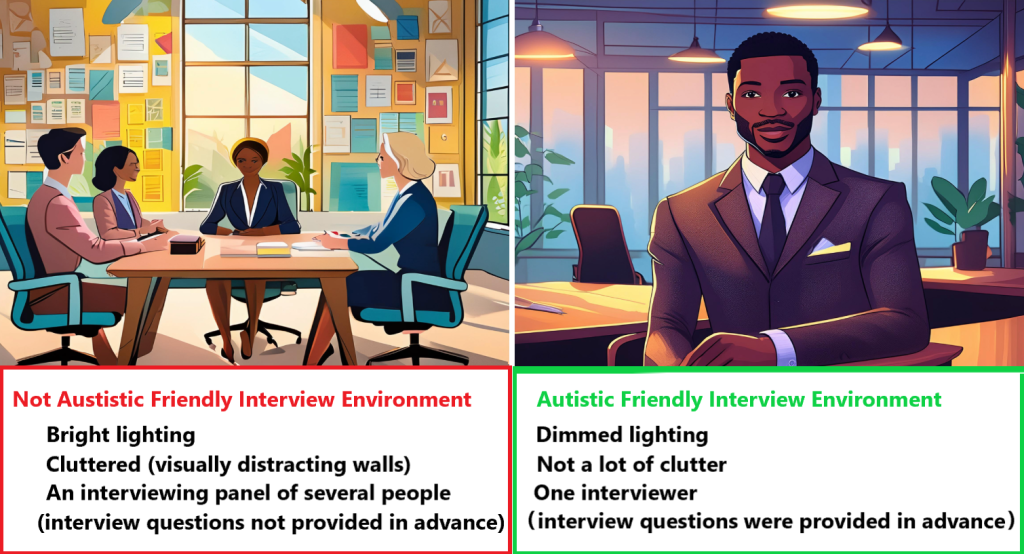

Qualified applicants are then given reasonable accommodations to interview. Some may interview from the emotional comfort of their respective homes. Others may have the interview questions emailed in advance. Applicants who are interviewed on site are greeted in quiet rooms with subdued lighting.

Applicants who are hired are then trained in the specific performance of their jobs. They are given literal expectations regarding their job performance by trainers who avoid the use of sarcasm and figurative language. These new employees are then assigned offices or cubicles that have light dimmers and are away from busy foot traffic.

When properly supported with reasonable accommodations, such employees have higher productivity and lower rates of turnover than those of allistic individuals.

In concluding, I would like to point out that autism is a spectrum disorder. All of us are different and all of us have varying strengths and weaknesses.

I myself was not diagnosed until rather late in life. I was clinically diagnosed with level I (described in psychology) as “high performing” autism in 2020 just a few months after I turned 60.

My autism has not prevented me from having spent 32 years in the classroom. I was an elementary teacher for 17 years and was a high school teacher for 15 years. I have a Master’s in Curriculum and Instruction, am currently working on special education certification, and once taught abroad at private American schools in Saudi Arabia and Beirut, Lebanon. I am also a trained chef with three years of industry experience.

To quote Temple Grandin who is arguably the best known autistic advocate, “I am different, not less.”

i myself have a son who was diagnosed at 19 months old and is now 18 and I could not be in more agreement with how you described the mindset of someone on the spectrum. Very well written

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike